Linear system of divisors

In algebraic geometry, a linear system of divisors is an algebraic generalization of the geometric notion of a family of curves; the dimension of the linear system corresponds to the number of parameters of the family.

These arose first in the form of a linear system of algebraic curves in the projective plane. It assumed a more general form, through gradual generalisation, so that one could speak of linear equivalence of divisors D on a general algebraic variety V.

A linear system of dimension 1, 2, or 3 is called a pencil, a net, or a web.

Contents |

Definition by means of functions

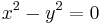

Given the fundamental idea of a rational function on a general variety V, or in other words of a function f in the function field of V, divisors D and E are linearly equivalent if

where (f) denotes the divisor of zeroes and poles of the function f.

Note that if V has singular points, 'divisor' is inherently ambiguous (Cartier divisors, Weil divisors: see divisor (algebraic geometry)). The definition in that case is usually said with greater care (using invertible sheaves or holomorphic line bundles); see below.

A complete linear system on V is defined as the set of all effective divisors linearly equivalent to some given divisor D. It is denoted |D|. Let L(D) be the line bundle associated to D. It can be proved that |D| corresponds bijectively to  [1] and is therefore a projective space.

[1] and is therefore a projective space.

A linear system  is then a projective subspace of a complete linear system, so it corresponds to a vector subspace W of

is then a projective subspace of a complete linear system, so it corresponds to a vector subspace W of  The dimension of the linear system

The dimension of the linear system  is its dimension as a projective space. Hence

is its dimension as a projective space. Hence  .

.

Base locus

If all divisors in the system share a common divisor, this is referred to as the base locus of the linear system. Geometrically, this corresponds to the common intersection of the varieties. Linear systems may or may not have a base locus – for example, the pencil of affine lines  has no common intersection, but given two (nondegenerate) conics in the complex projective plane, they intersect in four points (counting with multiplicity) and thus the pencil they define has these points as base locus.

has no common intersection, but given two (nondegenerate) conics in the complex projective plane, they intersect in four points (counting with multiplicity) and thus the pencil they define has these points as base locus.

Linear system of conics

For example, the conic sections in the projective plane form a linear system of dimension five, as one sees by counting the constants in the degree two equations. The condition to pass through a given point P imposes a single linear condition, so that conics C through P form a linear system of dimension 4. Other types of condition that are of interest include tangency to a given line L.

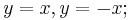

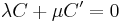

In the most elementary treatments a linear system appears in the form of equations

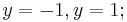

with λ and μ unknown scalars, not both zero. Here C and C′ are given conics. Abstractly we can say that this is a projective line in the space of all conics, on which we take

as homogeneous coordinates. Geometrically we notice that any point Q common to C and C′ is also on each of the conics of the linear system. According to Bézout's theorem C and C′ will intersect in four points (if counted correctly). Assuming these are in general position, i.e. four distinct intersections, we get another interpretation of the linear system as the conics passing through the four given points (note that the codimension four here matches the dimension, one, in the five-dimensional space of conics). Note that of these conics, exactly three are degenerate, each consisting of a pair of lines, corresponding to the  ways of choosing 2 pairs of points from 4 points (counting via the multinomial coefficient).

ways of choosing 2 pairs of points from 4 points (counting via the multinomial coefficient).

Applications

A striking application of such a family is in (Faucette 1996) which gives a geometric solution to a quartic equation by considering the pencil of conics through the four roots of the quartic, and identifying the three degenerate conics with the three roots of the resolvent cubic.

Example

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Type I linear system, (Coffman). | |

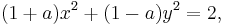

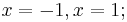

For example, given the four points  the pencil of conics through them can be parameterized as

the pencil of conics through them can be parameterized as  which are the affine combinations of the equations

which are the affine combinations of the equations  and

and  corresponding to the parallel vertical lines and horizontal lines; this yields degenerate conics at the standard points of

corresponding to the parallel vertical lines and horizontal lines; this yields degenerate conics at the standard points of  A less elegant but more symmetric parametrization is given by

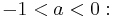

A less elegant but more symmetric parametrization is given by  in which case inverting a (

in which case inverting a ( ) interchanges x and y, yielding the following pencil; in all cases the center is at the origin:

) interchanges x and y, yielding the following pencil; in all cases the center is at the origin:

hyperbolae opening left and right;

hyperbolae opening left and right; the parallel vertical lines

the parallel vertical lines

- (intersection point at [1:0:0])

ellipses with a vertical major axis;

ellipses with a vertical major axis; a circle (with radius

a circle (with radius  );

); ellipses with a horizontal major axis;

ellipses with a horizontal major axis; the parallel horizontal lines

the parallel horizontal lines

- (intersection point at [0:1:0])

hyperbolae opening up and down,

hyperbolae opening up and down, the diagonal lines

the diagonal lines

- (dividing by

and taking the limit as

and taking the limit as  yields

yields  )

) - (intersection point at [0:0:1])

- This then loops around to

since pencils are a projective line.

since pencils are a projective line.

In the terminology of (Levy 1964), this is a Type I linear system of conics, and is animated in the linked video.

Classification

There are 8 types of linear systems of conics over the complex numbers, depending on intersection multiplicity at the base points, which divide into 13 types over the real numbers, depending on whether the base points are real or imaginary; this is discussed in (Levy 1964) and illustrated in (Coffman).

Other examples

The Cayley–Bacharach theorem is a property of a pencil of cubics, which states that the base locus satisfies an "8 implies 9" property: any cubic containing 8 of the points necessarily contains the 9th.

Linear systems in birational geometry

In general linear systems became a basic tool of birational geometry as practised by the Italian school of algebraic geometry. The technical demands became quite stringent; later developments clarified a number of issues. The computation of the relevant dimensions — the Riemann-Roch problem as it can be called — can be better phrased in terms of homological algebra. The effect of working on varieties with singular points is to show up a difference between Weil divisors (in the free abelian group generated by codimension-one subvarieties), and Cartier divisors coming from sections of invertible sheaves.

The Italian school liked to reduce the geometry on an algebraic surface to that of linear systems cut out by surfaces in three-space; Zariski wrote his celebrated book Algebraic Surfaces to try to pull together the methods, involving linear systems with fixed base points. There was a controversy, one of the final issues in the conflict between 'old' and 'new' points of view in algebraic geometry, over Henri Poincaré's characteristic linear system of an algebraic family of curves on an algebraic surface.

Line bundle/invertible sheaf language

Linear systems are still at the heart of contemporary algebraic geometry; but they are typically introduced by means of the ample line bundle language. That is, the language of sheaf theory is considered the most natural starting point, at least to learn the theory. In those terms, divisors D (Cartier divisors, importantly) correspond to line bundles, and linear equivalence of two divisors means that the corresponding line bundles are isomorphic.

See also

References

- ^ Hartshorne, R. 'Algebraic Geometry', proposition II.7.7, page 157

- Coffman, Adam, Linear Systems of Conics, http://www.ipfw.edu/math/Coffman/pov/lsoc.html

- Faucette, William Mark (January 1996), "A Geometric Interpretation of the Solution of the General Quartic Polynomial", The American Mathematical Monthly 103 (1): 51–57, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2975214, alternative download

- P. Griffiths; J. Harris (1994). Principles of Algebraic Geometry. Wiley Classics Library. Wiley Interscience. p. 137. ISBN 0-471-05059-8.

- Levy, Harry (1964), Projective and related geometries, New York: The Macmillan Co., pp. x+405

![[\lambda�: \mu]\](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/24c6d8ea805b5f3bd92c89fb882fbf8f.png)